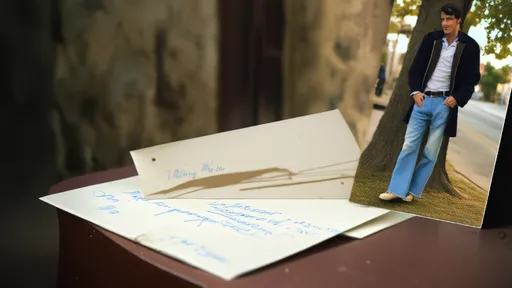

In the quiet corners of old albums and forgotten drawers, photographs fade with time. Their edges curl, their colors soften, and the faces they preserve grow indistinct. Yet sometimes, beside these relics of the past, new handwriting appears—notes scribbled in margins, names freshly inked, or stories retold in a different hand. These juxtapositions of fading images and new annotations speak to something deeply human: the tension between memory and reinterpretation, between what was and what we choose to remember.

There is an intimacy to handwritten notes that typed words cannot replicate. The pressure of the pen, the slight wobble of hurried script, the ink smudges—all these betray the presence of a living hand. When such writing appears beside an old photograph, it feels like a conversation across time. Perhaps a grandchild identifies a face their grandparents could no longer name. Or maybe an aging parent, sensing their own fading memory, hastily jots down details before they slip away forever. The act itself is an assertion: this moment mattered, and I will not let it disappear.

Photographs were once considered unassailable records of truth, but we now know better. Light leaks, chemical decay, and the biases of the photographer all shape what survives. A handwritten note beside a photo admits this fragility. It confesses that the image alone is not enough—that without context, without narrative, it risks becoming a beautiful cipher. The new ink is both a correction and a continuation, a way of saying, this is what I see now, this is what I need you to know.

Some annotations are practical—dates, locations, the full names that casual captions omit. Others are more lyrical, fragments of stories that the photograph alone cannot tell. A stern portrait might be softened by a later note: "He hated posing, but he laughed all the way home." A faded vacation snapshot gains new weight with the addition: "Our last trip together." The most poignant are those where the handwriting changes mid-thought, as if the writer paused, overwhelmed by the weight of memory.

Technology has altered this dynamic. Digital photos rarely fade, and metadata can store endless details invisibly. Yet something is lost when annotations are detached from the physical artifact. A pixel-perfect restoration of an old photo may preserve its clarity, but it cannot replicate the tactile history of a page handled by generations. The smudges, the creases, the faint scent of aged paper—these are part of the story too. Perhaps that’s why many still return to physical albums, adding their own marks to the collective archive.

In museums, conservators debate whether to restore artworks to their original glory or preserve the marks of age. Family photographs pose a similar dilemma. Do we attempt to halt their decay, or do we embrace the layers of time—the fading image, the yellowed paper, the new ink beside the old? There is no single answer, only the understanding that every intervention, every annotation, becomes part of the object’s history. The photograph is no longer just a record of a moment; it becomes a record of how that moment was remembered, and by whom.

The most haunting examples are those where the new writing corrects the old. A label reading "Our happy day" might be crossed out decades later, replaced with "I didn’t know yet." The photograph hasn’t changed, but its meaning has. Here, the fresh ink is not just additive but transformative, revealing how memory is never static. We don’t just recall the past—we reinterpret it, sometimes painfully, through the lens of all that has happened since.

Perhaps this is why we keep returning to those fading pictures and the notes beside them. They remind us that memory is not a vault but a conversation, one that continues as long as someone cares to add their voice. The photograph fades, yes—but the hand that writes beside it says: I am here now, and I remember it this way.

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025