In the quiet corners of traditional Chinese tea culture, there exists an unspoken reverence for the darkened interiors of well-used Yixing teapots. These purple clay vessels, born from the earth of Jiangsu province, carry more than just tea—they hold memories. The gradual accumulation of tannins and minerals creates what connoisseurs call "tea stains," but to dismiss them as mere residue would be to misunderstand their cultural significance entirely.

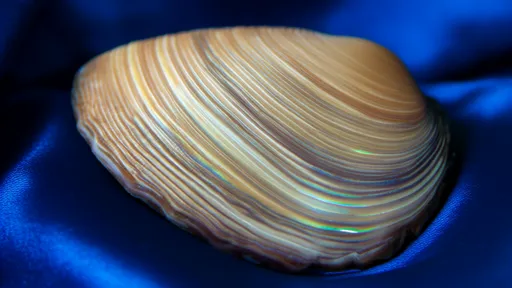

The relationship between a Yixing teapot and its owner unfolds like an epic poem written in steeped leaves. Unlike glazed ceramics that resist interaction, the porous zisha clay absorbs the essence of every brew. Over years of dedicated use, the interior develops a glossy patina that reflects not just light, but the very history of the teapot itself. This phenomenon transcends practical function—it becomes a living record of shared moments between human and object.

Seasoned collectors often speak of their teapots in surprisingly intimate terms. "This one remembers the winter of 1998," remarked Master Zhou, turning his prized shuiping teapot toward the light to reveal streaks of deep amber. "I was drinking ripe pu-erh every morning while writing my dissertation." The stains had preserved not just the tea's chemical signature, but the emotional context of its consumption. Such narratives reveal how these vessels become temporal markers in people's lives.

Western observers frequently misunderstand the value placed on these darkened interiors. Where some see uncleanliness, Chinese tea masters perceive cultivated beauty. The Japanese have their wabi-sabi, celebrating imperfection and transience, while Chinese tea culture embraces the conscious creation of patina as an art form. This difference in perception speaks volumes about cultural attitudes toward aging and the passage of time.

Scientific analysis of century-old Yixing pots reveals fascinating data about historical tea consumption patterns. The mineral deposits act as chemical archives, with mass spectrometry identifying traces of long-discontinued tea varieties. Researchers at Zhejiang University recently published findings showing how the patina layers in antique teapots correspond to known fluctuations in tea trade routes during the Qing dynasty. What appears as simple discoloration to the untrained eye becomes, under scrutiny, a palimpsest of economic and agricultural history.

The process of developing a quality patina requires patience and particular care. Enthusiasts debate proper maintenance techniques with near-religious fervor. Some advocate for never washing a teapot with soap, while others promote specific wiping methods using only boiled water and soft cloths. The common thread remains respect for the teapot as a living entity that grows more valuable with time—a radical concept in our era of disposable goods.

Contemporary artists working with zisha clay have begun exploring the aesthetic potential of intentional patina development. At a recent exhibition in Hangzhou, installation artist Liang Wei presented "Memory Vessels"—a series of teapots whose interiors bore artificially accelerated stains representing different emotional states. The most striking piece featured alternating light and dark bands, visually documenting six months of the artist's alternating depression and euphoria through his daily tea choices.

This cultural practice faces challenges in the modern world. The rise of ceramic and glass teaware, easier to clean and maintain, threatens the tradition of patina cultivation. Younger generations, raised with different values around hygiene and convenience, often prefer sparkling clean vessels. Yet a counter-movement persists among those who find profound meaning in these tea-stained interiors—a quiet rebellion against the cult of the new.

The true magic of Yixing patina lies in its ability to bridge past and present. When drinking from a well-seasoned pot, one participates in a continuum of experience that may span generations. The tannins deposited by a grandfather's favorite tieguanyin still influence the flavor of tea brewed by his grandchildren. In this way, the humble teapot becomes more than a utensil—it transforms into a family heirloom carrying flavorsome memories across decades.

As global interest in Chinese tea culture grows, so does appreciation for this nuanced aspect of teapot maintenance. International collectors now seek out properly "broken-in" Yixing pots, willing to pay premiums for vessels with authentic, well-developed patinas. Auction houses have begun including detailed photographs of teapot interiors in their catalogs, recognizing that for discerning buyers, the stains tell as much of the story as the clay itself.

Perhaps what makes the tea stain tradition so compelling is its quiet defiance of modern values. In a world obsessed with speed and novelty, the Yixing teapot asks us to slow down, to value gradual accumulation over instant gratification. Each layer of patina represents not just chemical compounds, but moments of pause, reflection, and connection. The darkened interior becomes a mirror reflecting our own relationship with time—if we take the time to look.

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025

By /Jul 15, 2025