The world of piano performance is rich with diverse schools of thought, each offering unique approaches to touch and technique. Among the most distinguished are the German-Austrian (Deutsch-Österreichische) and Russian schools, which have shaped generations of pianists. While both traditions aim for artistic excellence, their underlying philosophies and physical execution of touch reveal striking contrasts. These differences extend beyond mere aesthetics—they are rooted in biomechanics, pedagogy, and even cultural perspectives on sound production.

The German-Austrian approach emphasizes a weight-based technique, where the arm's natural weight generates tone rather than isolated finger strength. This method, pioneered by pedagogues like Ludwig Deppe and later refined by Theodor Leschetizky, fosters a relaxed yet controlled connection between body and keyboard. The fingers maintain close contact with the keys, with a preference for flatter finger positions that allow for seamless legato and a singing tone quality. The touch originates from subtle rotations of the forearm, creating what Germans describe as "Klang"—a resonant, harmonically rich sound that seems to emerge from within the instrument.

In contrast, the Russian school, developed through the lineage of Anton Rubinstein and perfected by Heinrich Neuhaus, favors a more articulated finger technique. Russian-trained pianists often employ higher finger action, with the digits striking the keys from above to produce brilliant, penetrating tones. This approach demands considerable finger independence and strength, particularly in the third phalanges. The resulting sound has laser-like projection—ideal for large concert halls—but requires meticulous control to avoid harshness. Where German pianists might visualize sound as flowing water, Russians often conceptualize it as sculpted marble.

Physiologically, these schools engage different muscle groups. The German-Austrian method relies heavily on the larger muscles of the back and shoulders, transferring energy through a supple wrist. This creates the illusion of effortless power, as seen in Wilhelm Kempff's recordings where fortissimo passages seem to resonate without percussive attack. Russian technique, meanwhile, activates the lumbricals and interossei muscles of the hand to achieve lightning-fast finger work, evident in the dazzling octaves of Richter or the crystalline articulation of Gilels.

Pedagogical tools further highlight these distinctions. German teachers might have students practice with coins balanced on their hands to cultivate relaxed weight transfer, while Russian instructors employ finger exercises resembling weightlifting—pressing down against resistance to build strength. The very language used differs: German methods speak of "Sinken lassen" (letting sink) while Russian texts emphasize "udar" (strike). These opposing metaphors shape students' neuromuscular development from their first lessons.

Contemporary research in piano biomechanics validates aspects of both traditions. Motion capture studies show that German-style arm weight produces more consistent key bed penetration—critical for tonal depth in Romantic repertoire. However, EMG data confirms that Russian finger articulation enables superior speed in passagework, explaining why Soviet-trained pianists dominated mid-20th century competitions. Interestingly, modern hybrids like the "Taubman Approach" attempt to reconcile these philosophies by incorporating rotational principles from the German school with Russian-derived finger alignment techniques.

The divergence extends to repertoire specialization. The German-Austrian touch thrives in Beethoven and Schubert, where structural clarity and voicing require nuanced weight distribution. Russian technique excels in Prokofiev and Rachmaninoff, demanding explosive accents and athletic leaps. Even in shared repertoire like Chopin, the contrast emerges: listen to Rubinstein's (Russian-school) heroic Polonaises versus Brendel's (Viennese-trained) poetically shaded Nocturnes.

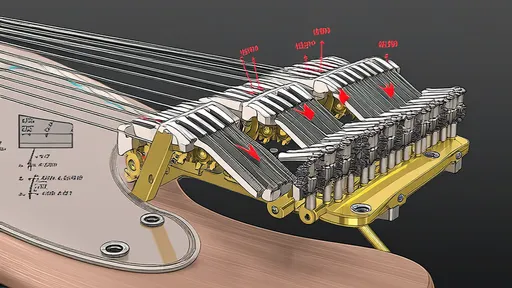

Instrument design historically reflected these preferences. Viennese action pianos of the 19th century had lighter touch resistance, complementing weight-based techniques. Russian manufacturers like Becker increased key dip and hammer weight to accommodate more vigorous playing. Today's concert grands attempt to balance these needs, though artists still modify touch accordingly—Barenboim reportedly adjusts his finger curvature when switching between Beethoven and Tchaikovsky.

Ultimately, neither approach holds absolute superiority. The German-Austrian method may produce more orchestral colors in Brahms, while the Russian school achieves unmatched virtuosity in Liszt. As globalization blends pedagogical traditions, understanding these physical differences helps pianists expand their technical vocabulary. The greatest artists—from Schnabel (German-trained) to Horowitz (Russian-educated)—demonstrated that technical means must serve musical ends, regardless of school. What remains universal is the pursuit of transforming physical motion into emotional resonance, whether through weighted cantabile or electrifying brilliance.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025