The revival of Baroque-era performance practices has long fascinated musicians and scholars alike, particularly when it comes to obscure or complex instruments. Among these, the theorbo—a double-necked lute with an extended bass range—stands as one of the most enigmatic. Its intricate design and specialized playing techniques have posed significant challenges for modern lutenists attempting to reconstruct its original sound. Recent efforts to decode its performance traditions, however, have yielded remarkable insights into how this instrument was once played, shedding light on a nearly lost art form.

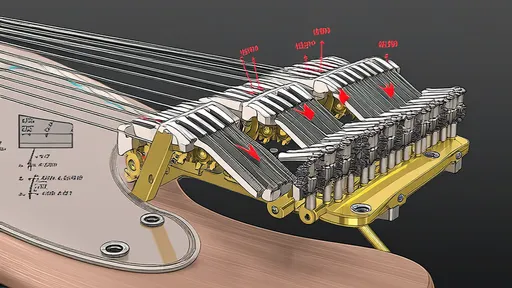

The theorbo’s unique construction demanded a highly specialized approach to both composition and performance. Unlike standard lutes, its extended second neck accommodated extra bass strings, often totaling up to fourteen courses. This design allowed for rich, resonant basslines, making it a favored continuo instrument in Baroque ensembles. Yet, the physical demands of playing such an instrument were considerable. The left hand had to navigate two separate sets of strings, while the right hand employed a combination of fingerpicking and strumming techniques that varied depending on the musical context.

Modern lutenists seeking to reconstruct these techniques have relied on a combination of historical treatises, iconography, and surviving instruments. One of the most critical sources is the 17th-century manuscript of Alessandro Piccinini, a virtuoso who composed extensively for the theorbo. His writings detail specific fingerings, string crossings, and even the angle at which the plectrum (or fingers) should strike the strings. These details, though seemingly minor, have proven invaluable in avoiding anachronistic playing styles that might otherwise distort the instrument’s intended sound.

Another challenge in reviving Baroque theorbo technique lies in the instrument’s tuning. Unlike modern lutes, which often adhere to standardized tuning systems, the theorbo’s strings were frequently adjusted to suit particular pieces or even individual passages. This flexibility allowed for greater expressive range but also required performers to develop an intimate familiarity with alternate tunings. Scholars now believe that many of the instrument’s most striking effects—such as its ability to mimic the human voice in slow, lyrical passages—were achieved through these subtle adjustments.

The role of improvisation in Baroque theorbo performance cannot be overstated. Unlike contemporary classical music, where notation is often treated as sacrosanct, Baroque musicians were expected to embellish and vary their playing in real time. This was especially true for the theorbo, which frequently served as both a solo and accompaniment instrument. Surviving accounts describe performers weaving intricate diminutions (ornamental variations) into their playing, a practice that required not only technical mastery but also a deep understanding of period-specific stylistic conventions.

One of the most intriguing aspects of the theorbo’s revival is the ongoing debate surrounding its timbre. While modern lutenists often strive for a clean, polished sound, historical evidence suggests that Baroque players may have embraced a grittier, more textured tone. The use of gut strings, as opposed to nylon, contributed to this quality, as did the occasional practice of deliberately allowing strings to buzz against the fingerboard—an effect that would be considered a flaw in most modern playing but may have been employed expressively in certain contexts.

As interest in historically informed performance grows, the theorbo has experienced something of a renaissance. Contemporary lutenists are increasingly incorporating these rediscovered techniques into their playing, often with startlingly authentic results. Workshops and masterclasses dedicated to the instrument have proliferated, and a new generation of musicians is pushing the boundaries of what we know about Baroque lute performance. The journey to fully reconstructing its original sound is far from over, but each new discovery brings us closer to hearing the theorbo as its first audiences might have.

Perhaps the most significant lesson emerging from this research is the importance of context. The theorbo was not merely a vehicle for notes on a page but an integral part of a broader musical ecosystem. Its techniques were shaped by the demands of the repertoire, the acoustics of the spaces in which it was played, and the collaborative nature of Baroque music-making. To truly understand how it was played, one must consider not just the mechanics of the instrument but the cultural and artistic milieu that gave rise to it.

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 17, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025

By /Jul 9, 2025